Foreign Investors Must Look before they Leap into the U.S.’s Thriving Real Estate Market by Arthur Dichter, JD, LLM

Posted on October 17, 2017

by

Arthur Dichter

Commercial and residential real estate in the U.S. continues to be a safe haven for foreign investors who seek the potential for higher yields and capital preservation than they may receive in their home countries or from portfolio investments. However, the potential upside from an investment in the U.S. real estate market comes with the costly risks of exposure to a complicated web of U.S. tax liabilities and reporting requirements. Failing to prepare in advance of one’s intention to invest in American assets can be quite costly.

Understand the Difference between U.S. Tax Status and Immigration Classification

A foreign person’s immigration status may be different from his or her tax status. Under U.S. tax laws, foreign individuals are considered resident aliens or non-resident aliens, depending on whether or not they meet certain tax residency thresholds.[1]

Nonresident aliens (NRAs) are required to pay U.S. taxes on income derived from U.S. sources. Net income from a rental property is generally subject to income tax on an annual basis. For NRAs, such income is taxed at graduated rates that may be as high as 43.4 percent, while a corporation (whether domestic or foreign) may face a 35 percent rate on such income. If real estate owned by an individual is sold after being held more than one full year, a reduced long-term capital gain tax rate will apply. There is no such reduced rate for a corporation.

NRAs or foreign entities that sell an interest in U.S. property may fall under the regulations of the Foreign Investment in Real Property Tax Act (FIRPTA), unless they qualify for an exception. FIRPTA requires property buyers to collect from sellers and pay directly to the IRS a withholding tax equal to 15 percent of the gross sales price. The IRS will consider the amount held back to be an NRA’s “deposit” on the income tax liability that he or she will generate from the sale of U.S. situs investment property, and the agency will apply that withholding amount as a credit against the seller’s final tax liability.

U.S. gift and estate tax will apply to NRAs who gift or donate U.S. situs property to another individual or to NRAs who die while owning U.S. situs property, regardless of whether the recipient or heir is a U.S. resident or a NRA. U.S. gift and estate taxes can be as high as 40 percent of the value of an NRA’s “U.S. situs” property that is located, or considered to be located, in the U.S. Unlike U.S. citizens and residents who have the ability to exclude $5.49 million from their taxable estates (or $10.98 million for married couples filing jointly), NRAs have a very limited estate tax exemption that protects only the first $60,000 of the value of their U.S. assets. This often leaves heirs of NRAs with a heavy and unexpected U.S. estate tax burden.

For gift and estate tax purposes, real estate located in the United States will always be considered U.S. situs property as will stock of a U.S. corporation.

Choose the Right Structure to Hold U.S. Real Estate

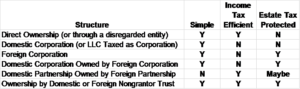

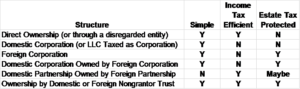

The tax consequences of investing in U.S. real estate depend largely on the way that the property is held. The goal of trying to minimize the impact of income taxes often conflicts with the goal of estate tax protection. A structure that provides for an opportunity for the reduced long-term capital gain tax rate may not protect the foreign investor from U.S. estate tax. Similarly, inserting an entity to “block” the U.S. estate tax may result in higher taxes on a gain due to the unavailability of the long-term capital gain rate. Unfortunately, there is no perfect structure, and foreign investors must work with experienced advisors who can help them navigate among the various options, each of which provides a different level of complexity, tax efficiency and risk.

Personal Ownership of Property

The least complex structure for an NRA to acquire U.S. property is in his or her personal name. If the NRA rents out personal property, he or she will be required to file annual U.S. income tax returns to report income or loss from such activities. However, if the property is solely for personal use, the NRA will typically not have a U.S. tax or reporting requirement until he or she sells the property. If the property is held for more than a year, the capital gain rate will apply upon sale. However, if the NRA dies while owning U.S. situs property, the value of the property that exceeds $60,000 will be subject to the 40 percent U.S. estate tax, as well as potential state-level estate or death tax. Often, an NRA will be advised to hold U.S. real estate through a single-member limited liability company (LLC). While holding the property through such an entity may provide the benefits of liability protection, absent a special tax election, such an entity is “disregarded” for income and estate/gift purposes and would not provide any protection against the estate tax.

Holding U.S. Property in a Legal Structure

The United States offers foreign investors a number of different entities to use for ownership of U.S. real estate. Primarily, these include a corporation, partnership[2] or trust structure.

Corporate Structures. Holding property in a domestic corporation is simple. U.S. tax law considers the corporation to be a separate legal entity that is required to file an annual income tax return and report the property’s yearly activities, which may include rental income or taxable gains in the year that the corporation sells the property. Losses generated from rental activities may be deductible. Losses that cannot be used currently may be carried forward and used to reduce the gain on an eventual sale. FIRPTA withholding should not apply.

Despite its simplicity, a corporate structure is typically not tax efficient. Income or gain from the sale of the property will be subject to tax at the highest corporate tax rate. Further, stock of a domestic corporation is a U.S. situs asset for U.S. estate tax purposes, and the estate of an NRA who dies while owning stock of a U.S. corporation will be subject to estate tax on the value of the stock that exceeds $60,000.

NRAs also have the option to own U.S. real estate in a foreign corporation. Similar to a domestic entity, the foreign corporation would be subject to taxes on its activities. Income and gain would still be subject to the high corporate income tax, and FIRPTA withholding would apply to a sale.[3] However, the value of the property would not be subject to U.S. estate tax because stock of a foreign corporation is not U.S. situs property, even if the foreign corporation only owns U.S. situs assets.

The most common structure for owning U.S. real estate involves the use of a foreign corporation, which owns a domestic corporation that owns the U.S. real estate. Although this option is slightly more complex and not tax efficient, it is still relatively simple and provides estate tax protected.

Partnership Structure. An entity treated as a domestic or foreign partnership[4] typically is not considered a separate taxpayer for U.S. income tax purposes. Rather, each partner is subject to tax on his or her pro rata share of the entity’s income. As a result, if a partnership has a long-term capital gain from the sale of U.S. real estate, its NRA partners will benefit from the long-term capital gain tax rate. A complex set of withholding rules apply to a partnership with foreign partners.

Although tax efficient, this structure is very complex and requires the filing of multiple tax returns. Further, the structure involves risk. The law is surprisingly unclear in regard to whether an interest in a partnership is a U.S. situs asset for estate tax purposes. While many practitioners believe that an interest in a foreign partnership that owns an interest in a domestic partnership should not be considered a U.S. situs asset for estate tax purposes, there is no specific authority that addresses this issue nor is the outcome certain. Many other practitioners believe that there is a significant risk that the IRS will take the position that the partnership interest is U.S. situs property. This structure is advisable only where the NRA is comfortable with the level of complexity and risk.

Trust Structure. A final option available to NRAs is the creation of a trust structure to buy and hold U.S. real property, usually through a disregarded LLC. A trust may be subject to income tax itself, or its beneficiaries may be subject to tax to the extent the trust makes distributions. The long-term capital gain rate generally applies. When a trust is properly structured, the assets may escape gift and estate taxes as well as the public and costly process of probate. While a properly structured trust is simple, tax efficient and estate-tax protected, there are many traps that the unwary can fall into without careful drafting and planning.

Conclusion

Investing in U.S. real estate should be done under the guidance of experienced tax and legal professionals in order to minimize investors’ tax risks and properly accumulate costs throughout the life of the property. There are a multitude of strategies individuals may employ to minimize their exposure to U.S. income, estate and tax liabilities. Each must be weighed against the related costs and risks, as well as the individual investor’s unique circumstances.

The advisors and accountants with Berkowitz Pollack Brant Advisors and Accountants have developed a global reputation for helping foreign individuals and businesses navigate the complex world of U.S. tax laws.

About the Author: Arthur Dichter, JD, is a director of International Tax Services with Berkowitz Pollack Brant, where he works with multi-national businesses and high-net worth foreign individuals to structure their assets and build wealth in compliance with U.S. and foreign income, estate and gift tax laws. He can be reached at the CPA firm’s Miami office at (305) 379-7000 or via email at info@bpbcpa.com.

[1] A NRA is an individual who is not a U.S. citizen or a U.S. tax resident. For income tax purposes, an individual will be considered a U.S. tax resident if they are admitted as a permanent resident (the green card test) or they meet a test based on physical presence (the substantial presence test). For estate and gift tax purposes, a person other than a U.S. citizen will be considered a U.S. resident if they are domiciled in the United States. Rather than physical presence, domicile considers the more subjective test of “intent” to remain in the U.S. for an indefinite period time.

[2] A limited liability company may be treated as a corporation, a partnership, or it may be disregarded as an entity separate from its owner depending on the number and personal liability of the members and whether it has made an “entity classification” election for tax purposes.

[3] Any net income that the foreign corporation has may also be subject to a second level of “branch profits” tax, which is similar to what would apply if the foreign corporation were a domestic corporation and paid a dividend to its shareholder.

[4] A foreign entity will be treated as a partnership if it does not meet the Tax Code’s definition of a “per se corporation” and it does have more than one member, all of whom have limited liability However, there is an opportunity for certain entities that do not meet this “default” definition to elect treatment as a partnership for U.S. income tax purposes.

← Previous